He is always interesting, and at his best a great writer. He wants no distractions from his target. In this passage, from A Handful of Dust, we feel Waugh concentrating on the character mercilessly. He ate in a ruthless manner, champing his food (it was his habit, often, without noticing it, to consume things that others usually left on their plates, the heads and tails of whiting, whole mouthfuls of chicken bone, peach stones and apple cores, cheese rinds and the fibrous parts of the artichoke.) “Besides, you know,” he said, “it isn’t as though it was all Brenda’s fault.” He clearly had more to say on the subject and was meditating the most convenient approach. (Has anyone ever described transient physical concern so easily?) Here is his description of a selfish brother-in-law trying to get the best deal for his sister in her divorce settlement and thereby save himself financial trouble: Waugh might have admired this passage, but he would never have written its combination of old-fashioned verbal limbs like “fog of mystery” and elusive razor blade image. Once more Beach, with that lucid brain of his, had dispelled the fog of mystery which had threatened to defy solution.” Wodehouse wrote in a strange, baroque manner that is unique in English prose: “The puzzled frown that had begun to gather on Lord Emsworth’s forehead vanished like breath off a razor blade.

Wodehouse (a writer he greatly admired), their styles have little in common. Helena is not that kind of book.Īlthough he is frequently mentioned in relation to P.G. In books like Decline and Fall (1928), Black Mischief (1932 ), A Handful of Dust (1934), Scoop ( 1938 ), Put Out More Flags (1942 ) and his World War II novels, he brings to life dozens of funny characters from the British upper and middle classes who have the element needed for comic success in that type of book: they are believable but absurd, and the absurdity contributes to the believability-there is no seam in the garment that Waugh offers us. Among modern writers in English only Ernest Hemingway, with whom he had a good deal in common, and William Faulkner created fictional voices as recognizable.

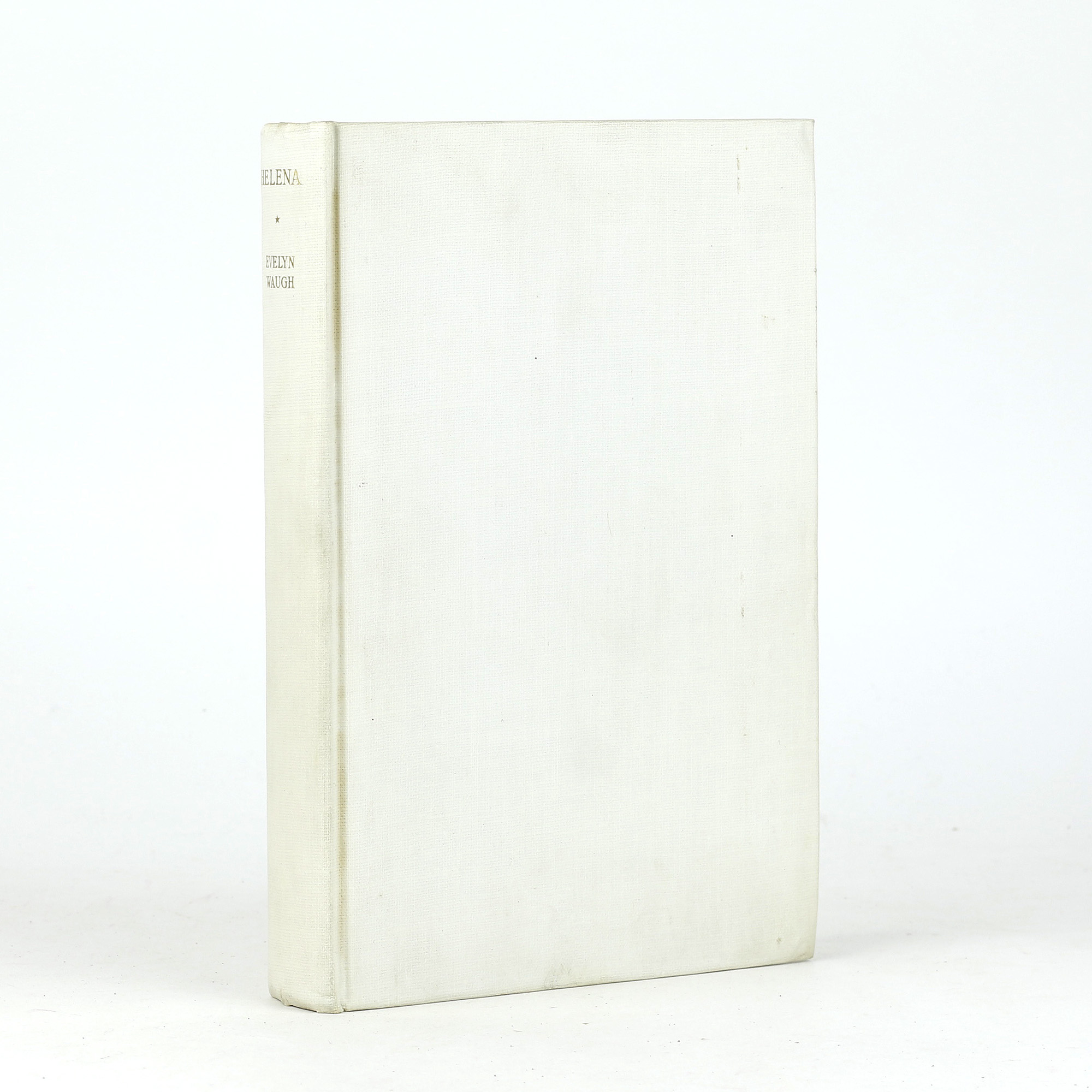

Waugh wrote a half dozen of the funniest books in English, in a clear, forceful style that is as distinct as that of any twentieth-century British writer. Helen, mother of Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor, appears at first an anomaly in his career. Although Evelyn Waugh was a Catholic, Helena (1950), his novel about St.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)